Stephen Maher. The Prince: The Turbulent Reign of Justin Trudeau. Simon and Schuster Canada, Toronto, 2024.

385 pp.

By Matthew Rowley

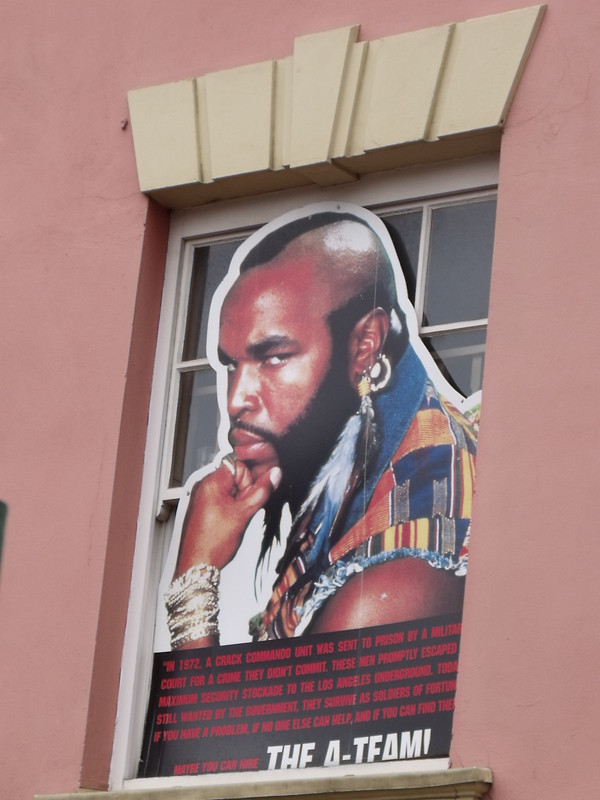

Reading Stephen Maher’s fascinating new book on Justin Trudeau, it’s tough not to be reminded repeatedly of the A-Team. The A-Team was a classic TV show. A group of mercenaries do good and defeat the baddies in every action-packed episode of this memorable bit of 1980’s nostalgia.

The A-Team team was made up of Hannibal, the planner and organizer – the one who comes up with the scheme that the others will put into action, H.M. (Howling Mad) Murdoch, the pilot and all-around force of nature who gets things done, and B.A. (Bad Attitude) Baracus, the heavy man, strong in a fight and good with vehicles, played by the incomparable Mr. T.

Then there was Templeton (Faceman) Peck, the guy who has a pretty face, is good with the ladies, and can smooth-talk his way through anything. His skill is to bluff and BS his way through, using only his good looks and charm. Once the real thought-work and action happens, he is no longer much use to the team.

While there are people in the background of the Trudeau story with skills and abilities, what we see in Trudeau is a modern-day Faceman, one who can look good and talk fast (so long as he has a good script), but who does not have the abilities or attention span necessary to deal with running a government.

While there are people in the background of the Trudeau story with skills and abilities, what we see in Trudeau is a modern-day Faceman, one who can look good and talk fast (so long as he has a good script), but who does not have the abilities or attention span necessary to deal with running a government.

As Steve Verheul, who worked with both Stephen Harper and Justin Trudeau, states it, Trudeau “sees a big part of his job being he’s the public face. He’s for the delivery of the messages, he’s for overall guidance, not someone that gets into the fine, fine details of issues.”

The office of Prime Minister as it has emerged from centuries of constitutional development, in Great Britain and here in Canada was never intended to house the chief communications flack of the national government. But the picture revealed in this book portrays Prime Minister Justin Trudeau as simply nothing more.

Maher, a seasoned journalist and writer, provides a detailed study of Trudeau’s life, especially focusing on the eras of Trudeau’s political career. He begins by relating the anecdote of Trudeau announcing his first cabinet, which was gender balanced, something the government was keen to make a big deal about. When asked why he did it, Trudeau provided the empty answer “because it’s 2015.”

Maher uses this story to talk about the hope and excitement that many Canadians felt as Trudeau entered government on a promise of ‘sunny ways,’ a new way to do business, a government that truly cared. Trudeau was going to be “a handsome, smiling prince, ready to lead Canadians away from the divisions of the Stephen Harper years toward a progressive future.”

Maher’s story tracks the rise of Trudeau from an unserious person, friendly and open with people, but lacking real accomplishments, to an unserious prime minister, walled off and closed to people, leaning on others’ accomplishments.

Maher speaks as one who encountered Trudeau throughout his adult life, watching the rise of this skateboarding MP through his early days on Parliament Hill to his current position as leader of the Canadian government and representative of Canadian values on the world stage. From the start Maher thought that he was “like a prince,” the key line that he uses in framing the book.

As he tracks Trudeau’s journey, he provides a catalogue of the (limited) successes of his government, such as the signature Canada Child Benefit, or key legislative victories like marijuana legalisation and the implementation of the Carbon Tax.

Maher also provides a thorough listing of the failures, flaws, and faux pas that have attended the Trudeau years. He shows Trudeau to be able to build a team, but also to be unafraid of throwing someone off (or under) the bus if they are not furthering his ends. Trudeau is revealed to be an effective person in front of the cameras, but also someone prone to gaffes and undisciplined behaviour if left to himself and not carefully managed. He is shown to be trainable, but also to fall back into his bad habits if he is not regularly drilled in what he is supposed to be doing. He is revealed, as in Paul Wells’ recent book, to be one who promises the moon but routinely falls short in delivering. All these things and more are brought to the fore as Maher takes the reader on a detailed journey through the political life and times of Justin Trudeau.

Maher seems to have had excellent access to Trudeau’s cabinet and caucus colleagues, as well as a plethora of political and other people across Canada. The result is a thorough portrait of Trudeau, The portrait that emerges is by no means positive, as those who know Trudeau intimately present an unflattering picture of the man behind the face.

While diagnosis of mental disorder is dangerous for non-practitioners to do, there are several former and current colleagues who have done just that: “I think he is narcissistic,” says one of his former ministers.

While diagnosis of mental disorder is dangerous for non-practitioners to do, there are several former and current colleagues who have done just that: “I think he is narcissistic,” says one of his former ministers, “I think he truly believes that he is needed by Canada, has done great things to save Canada.” Another former minister said, “Trudeau has gotten to a place now where he actually believes that he is doing good for the country, irrespective of anything else, which I think is hugely scary and problematic.”

Maher quotes the Mayo Clinic definition of narcissism to support the idea that one could indeed find such a problem at the core of Trudeau’s character. Most fascinating in Maher’s discussion of this issue is the attempt by some close to the Prime Minister to confirm his narcissistic behaviour and yet declare it to be a positive thing. “Do you know any prime minister who wasn’t a narcissist? I mean, how do you win? How do you ever decide you should be prime minister?” It is a fascinating window into the minds of those who support Trudeau in his Prime Ministerial role.

Trudeau is further exposed as someone who is confident about what he thinks, whether it is backed by truth or not. “He had a similar certainty about matters where he didn’t know what he was talking about. It reflected the immaturity of an academic dilettante, someone whose opinions were always greeted with interest because of his charisma and family name but who lacked the intellectual discipline for which his father was famous.”

This combination of self-focus and confident ignorance is shown to lead to the kind of unforced errors, blunders, and outright scandal that have dogged the Trudeau government throughout its long tenure in office.

This combination of self-focus and confident ignorance is shown to lead to the kind of unforced errors, blunders, and outright scandal that have dogged the Trudeau government throughout its long tenure in office.

It is no secret that Stephen Maher, at least in general terms, agrees with many of the progressive ideas and attitudes espoused by the Liberal Party of Canada, as evidenced by his columns in national newspapers and magazines, as well as the book itself. There is very little daylight between the author and the Liberals when it comes to their outlook on climate change, the Freedom Convoy, or Trudeau’s approach to reforming the Senate.

Despite Maher’s ideological alignment on many issues, he presents the facts of the Trudeau story effectively, with devastating results.

Where this reviewer sees a Faceman, Maher sees a prince, one who was ‘to the manor born,’ the manor in this case, being 24 Sussex Drive. A prince with a family name as potent as the Bourbons, the Medici’s, or the Tudors in their day, a name that is recognized around the world. As he grows up, first in the home of the national leader, and later in the salons of Laurentian power, the prince soon discovers that he can always get by on privilege, his natural good looks, and style.

As a prince he confidently steps into situations, sometimes showing bad judgement and impatience. Maher relates the story of Trudeau’s elbow hitting NDP MP Ruth-Ellen Brousseau as he manhandled the Conservative Whip to his chair to start a recorded vote in Parliament in 2016. He struggles to control his mouth, as when he cursed at a member in the House of Commons. He refuses to listen to wise advice, as when he chose to go to the Aga Khan’s Island for an all expense paid luxury vacation, despite the strenuous objections of his staff. He can be brutally cold to those who displease him, whether it is throwing his own brother off the bus or throwing the first Indigenous female justice minister out of her job for daring to challenge him. Anyone who gets in his way is ruthlessly cast aside, no matter what hurt it causes.

What strikes the reader as they make their way through this thoroughly-researched work is just how much help Trudeau has needed to get to the top and stay there. Trudeau has always had close friends around him who have done the heavy lifting to propel him to the next height.

What strikes the reader as they make their way through this thoroughly-researched work is just how much help Trudeau has needed to get to the top and stay there. Trudeau has always had close friends around him who have done the heavy lifting to propel him to the next height.

Gerald Butts, a lifelong friend, provided not merely political help but really was a central figure in engineering Trudeau’s rise to power. Katie Telford, Trudeau’s long-serving Chief of Staff is revealed to be the key driving force in the government. Maher describes them as a triumvirate and he points out that Butts’ drive on economic issues and Telford’s drive on progressive issues have shaped the policy decisions of the government. Butts and Telford are revealed to have been the key communicators and policy drivers with cabinet relations, insulating the prime minister from contact with the people actually running government ministries.

Maher writes that the departure of Gerald Butts over the government SNC Lavalin scandal meant the government would “lose its central focus on inequality—the middle class and those working hard to join it—and focus more on the feminism and diversity issues that Telford embraced.”

Throughout Maher’s book Trudeau is revealed to be short on his capacity to understand and manage fine details and policy, preferring to leave those things to his staff, particularly Butts and Telford, essentially confirming the role of Trudea as Faceman to the Butts-Telford team.

As a result, in stark contrast to Trudeau’s 2015 declaration that “government by cabinet is back,” power has been ever-increasingly concentrated in the PMO. “Compared to previous prime ministers, who would regularly have dinners and one-on-one meetings with their ministers, Trudeau had to outsource Cabinet management to Butts and Telford.”

Maher shows that Trudeau’s introversion and unwillingness to deal with individuals is revealed to be a crippling weakness that precludes effective leadership and makes him merely the face man in a government run by more competent individuals. Maher further examines Trudeau’s overriding desire to be liked – an obsessive personality trait that overwhelms all consideration of good policy, turning the whole government into a PR instrument for his own personal brand.

As a writer, Maher is easy to read and he clearly has close insights into his subject matter. Maher does not have a problem inserting his own opinion and evaluation into his work, – making, at times, highly emotional statements – or describing his own insights into what he thought about Trudeau as he reported on him over the years.

It is good that Maher shows his biases, but the reader must remember that Maher is not writing as a totally impartial arbiter. This is a noticeable contrast to Paul Wells’ recent biography of Trudeau, where Wells worked very hard to keep opinion out of the book. Though Maher is disciplined throughout the majority of the work, his personal outlook routinely flavours his writing.

At several points in the book, Maher reveals his strong political proclivities, such as embracing the notion that Trudeau created a non-partisan group in the Senate when he ejected Liberal Senators from his Parliamentary caucus.,His laudatory comments about the CERB program essentially ignore the serious inflation and workforce problems that still plague the nation.

Maher also admits to passing along Trudeau’s talking points in the manner that has fueled general contempt for much of the Parliamentary Press Gallery: “I reported his comments [on first-past-the-post voting], but I did not believe him—and as things turned out, I was right not to believe him.”.

It will also be difficult for western Canadians to stomach the casual slurs embedded in some of his commentary, for example, on energy policy: “many westerners see the carbon tax as a dirty eastern plot dreamed up by the family who brought them the National Energy Program,” or “Westerners accused Trudeau of preventing them from putting bread on the table and Maseratis in their driveways.” Such casual gibes, that cross the line into base viciousness, show a blind spot that is widespread in Laurentian circles. The grievances of westerners are seen as imaginary, arising from ingratitude, and an inability to work with the rest of the country or strive for higher things.

The A-Team is out of gas.

Elliiott Brown – The 80’s Bar / Reflex – Formerly The Crown Public House, Broad Street, Birmingham – Mr T – The A-Team – CC by 2.O license

Maher’s book is perhaps an unintended masterpiece, tracking the rapid rise and painful, agonizing fall of a princely showman. Maher presents a rosy picture of Trudeau at the beginning of his leadership of the Liberal Party: “Against the odds, Trudeau and his people had built a formidable political machine around the son of Canada. He was accident-prone, but hard-working, resilient, and confident, and Canadians felt they knew him. He had good instincts, had gathered a team of talented people around him, and crucially, was listening to them, working on his skills, applying himself, getting better. He was ready for an election and looking to prove himself.”

By the end of the story, Maher gives a very different outlook on Trudeau, quoting Don Martin from CTV: “He has become too woke, too precious, preachy in tone, exceedingly smug, lacking in leadership, fading in celebrity, slow to act, short-sighted in vision and generally getting more irritating with every breathlessly whispered public pronouncement.”

The A-Team is out of gas. The Faceman is no longer able to swoop in and fix it with smooth talk and a pretty face. He has thrown the other team members off the bus, and now he finds himself isolated, enervated, and unloved by an electorate who have seen through the smooth talk and saccharine showmanship to the hollow man underneath.

In tracking the arc of Justin Trudeau’s years as Prime Minister, from entitled and confident prince, to tarnished and tired Faceman, Maher has given us an excellent glimpse into the inner workings of Justin Trudeau’s mind, his life and his government.

Matthew Rowley is president of Training Leaders International Canada, an overseas teaching organization. He holds a Bachelor of Theology from Clearwater College, an MDiv from Canadian Southern Baptist Seminary, and a PhD from McMaster Divinity College. His scholarship is heavily focused on the early development of the Canadian political, church, and educational systems, and he works to educate people on the history and philosophy of conservatism. He currently resides in Water Valley, Alberta.